Western misunderstandings of ‘one country, two systems’

Lau Siu-kai – China Daily

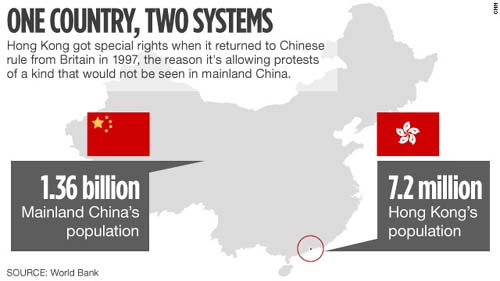

Since Hong Kong’s reunion with the Chinese mainland in 1997, the practice of “one country, two systems” in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region has been incessantly and unrelentingly criticized by Western politicians, media, opinion leaders, NGOs, human rights organizations and international bodies dominated by the West.

Recently, some Westerners have even claimed that “one country, two systems” is dead. Undeniably, some of the “criticisms” have ulterior motives and are part and parcel of the Western strategy to weaken, isolate and contain the rise of China as well as to undermine Hong Kong’s economic significance to the country.

In fact, most of the “criticisms” are derived from deliberately distorted interpretations of “one country, two systems”, and hence are groundless and unfair. Because of these distortions and their impact on the policymakers, many policies of Western nations toward Hong Kong are misguided and detrimental not only to Hong Kong but also to their own interests.

Simply put, ten pitfalls in the understanding of “one country, two systems” by the West can be gleaned from Western narratives and criticisms of Hong Kong over the years:

Seeing the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong as the source and basis of “one country, two systems” and the Basic Law of Hong Kong. In fact, on the contrary, “one country, two systems” was China’s policy toward post-1997 Hong Kong made well before Sino-British negotiation over “Hong Kong’s future” and was enshrined in the Constitution of the PRC, approved by the National People’s Congress in 1982. As such, the origin and legitimacy of “one country, two systems” has nothing to do with the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which deals primarily with Hong Kong’s reversion to China. Nor is “one country, two systems” the outcome of British pressure on China. After China has incorporated its proclaimed policy toward Hong Kong in the Joint Declaration into the Basic Law, the legal obligation of China toward the Joint Declaration is fulfilled, and the Joint Declaration thereafter becomes only a historical document. Britain would have no so-called “moral obligation” to Hong Kong, and Britain, let alone other Western countries, has no legal right to dictate how China handles Hong Kong affairs. Besides, given the paramount importance of national sovereignty to China, it can hardly be envisaged that China would leave room in the Joint Declaration for Britain to interfere in Hong Kong affairs after 1997.

Irrespective of the fact that Hong Kong is an integral part of China, the West still wrongly sees Hong Kong as a special place in China necessitating protection by the West. The West tends to see Hong Kong as an “independent political entity” and still considers it a member of the Western camp. The West continues to expect Hong Kong to serve the West’s interests in containing China’s rise or in promoting regime change in China. Accordingly, the West gives encouragement and support to the anti-China and anti-communist elements in Hong Kong, undermining its stability and effective governance.

Misinterpreting Hong Kong’s “high degree of autonomy” as “absolute autonomy”. The powers and responsibilities of the central government over Hong Kong are not recognized, and any exercise of its legitimate powers by the central government is heavily lambasted by the West.

Under the misconception that Hong Kong enjoys “absolute autonomy”, the West accordingly denies that Hong Kong has the duty to legislate on Article 23 of the Basic Law to safeguard national security. Nevertheless, as a matter of fact, that Hong Kong should avoid turning into a base of subversion against China is the precondition for Hong Kong to be granted a high degree of autonomy by Beijing under “one country, two systems”. The irony here is that on the one hand the West urges China to faithfully abide by the Basic Law, and on the other hand the West would castigate China for demanding Hong Kong to legislate on Article 23.

Casting aside the Chinese Constitution and failure to see that Hong Kong’s post-1997 constitutional order is constituted by both the Constitution of the PRC and the Basic Law of the HKSAR. As a result, whenever Beijing makes decisions or laws for Hong Kong using powers granted by the Constitution (such as the National Security Law), the West invariably exhibits unjustifiable fits and outbursts.

Seeing democratic development as the primary purpose of “one country, two systems” and the Basic Law and losing sight of the much more important goals in the mind of Beijing. The urge of the West to “export” its “democratic model” to Hong Kong runs against the determination of Beijing to safeguard national sovereignty, national security and territorial integrity. The West’s failure to understand that Hong Kong’s democratic development must be compatible with the needs and purposes of “one country, two systems” has resulted in a situation where democratic progress and political stability in Hong Kong have been unnecessarily hampered by the stupid and hasty moves of some “pan-democrats” doing the bidding of the West.

Seeing that “one country, two systems” is designed solely to cater for the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong and failing to appreciate that it is basically a “China first” policy. The innovative system arrangement is devised primarily for the sake of national unification and development, but Beijing will still make maximum efforts to maintain Hong Kong’s prosperity and stability after 1997. By overestimating Hong Kong’s importance to China, the West has oftentimes committed the mistake of believing that China will succumb to the political demands of the West and its followers in Hong Kong if the West threatens to sanction China and its Hong Kong SAR. But not only will China resist the West’s demands, it will also take countermeasures, which would jeopardize the West’s interests in Hong Kong and in the Chinese mainland.

Seeing the common law as the only way to interpret the Basic Law, ignoring the fact that the Basic Law is a national law in China’s socialist legal system, denying the Standing Committee of the NPC as the highest authority in interpreting the Basic Law and “one country, two systems”, and denigrating the legal expertise and integrity of the legal practitioners on the Chinese mainland. Accordingly, any interpretation of the Basic Law by the NPCSC is seen and criticized by the West as “infringement” of the Basic Law, the independence of the Hong Kong judiciary and the integrity of Hong Kong’s legal system. Such disrespect for the Chinese legal system would only fuel the tensions between China and the West over Hong Kong.

Seeing the increasingly close economic and trade relationship between Hong Kong and the mainland as the erosion of Hong Kong’s autonomy and providing Beijing with more channels to tamper with Hong Kong affairs. Nevertheless, in the original design of “one country, two systems”, Hong Kong is expected and even “called upon” to forge increasingly close ties with the mainland so that Hong Kong can benefit from the nation’s development while contributing to the mainland’s reform and opening up by means of its special and irreplaceable advantages stemming from its capitalist system. “One country, two systems” does not stipulate economic separation of Hong Kong from the mainland.

Demonizing any form of education in Hong Kong on the Constitution, the Basic Law, national identity, history and culture as “brainwashing” and “harmful” to “one country, two systems”. On the contrary, successful practice of “one country, two systems” in Hong Kong requires its people to know China better, identify with the nation more, understand Beijing’s policy toward Hong Kong more thoroughly and accept Hong Kong’s obligations to the country more willingly.

In the days ahead, in view of the West’s longstanding distortions of “one country, two systems” and the Basic Law and their adverse influence on the international community as well as on some sections of the Hong Kong populace, these pitfalls on the part of the West have to be countered effectively and robustly for the sake of smooth and successful implementation of “one country, two systems” in Hong Kong.

The author is emeritus professor of sociology at The Chinese University of Hong Kong and vice-president of the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macao Studies.