The curious story of Rome’s talking statues

Liaquat Ali

The tradition of Rome’s talking statues dates back to the 16th century when the city’s resident began to show their discontent against the oppressive power of the papacy with anonymous epigrams and satirical verses poking fun at religious and civil authorities.

These irreverent notes, written as if spoken by the statue, were affixed at night to avoid the author getting caught, and were read with hilarity by passersby the next morning before being removed.

Stendhal noted on his visit to Rome in 1816: “what the people of Rome desire above all else is a chance to show their strong contempt for the powers that control their destiny, and to laugh at their expense.”

The best known of Rome’s talking statues is Pasquino, near Piazza Navona, which remains in use to this day and is regularly plastered with political messages and even small advertisements. However there are five other statue parlanti among the so-called “Congregation of Wits”.

Pasquino

Located in the piazza of the same name, this damaged statue from the third century BC probably came from the Stadium of Domitian in what is today Piazza Navona. The caustic verses that Roman poets and thinkers attached to Pasquino were hugely popular and resulted in the term “pasquinade”.

The popes of the day were irritated at being the butt of criticism, with Adrian VI allegedly talked out of his plan to have the statue thrown into the river Tiber, while Pope Benedict XIII took a harder line in 1728 by issuing an edict condemning anyone caught posting pasquinades on the statue to death. Pasquino was eventually put under surveillance at night to stop the practice, prompting Romans to seek other statues to vent their frustration and sarcasm.

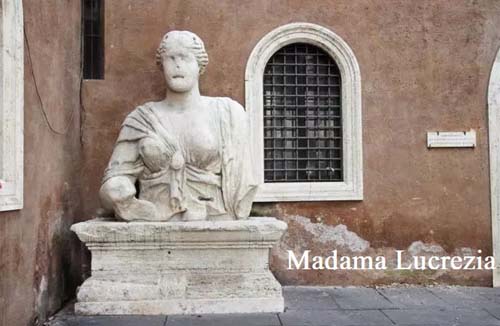

Madama Lucrezia

Rome’s only female talking statue, Madama Lucrezia is a large Roman bust, probably representing a priestess of Isis or even the goddess herself. The three-metre high statue sits on a plinth in a corner of Piazza S. Marco, just off the central Piazza Venezia.

It is thought that the badly-disfigured statue got its popular nickname in reference to the noblewoman Lucrezia D’Alagno, the mistress of Alfonso d’Aragona, King of Naples. She moved to Rome after the king’s death in 1458 and lived in the present-day Palazzo Venezia outside which the statue is located today.

Marforio

This colossal statue dating from the first century AD can be found today in the courtyard of Palazzo Nuovo in the Capitoline Museums. Representing a male divinity or river god – identified variously as Neptune, Jupiter or the Tiber – the bearded Marforio was originally sited near the Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum.

Its name may derive from “Mare in Foro” or from the Marfuoli family which owned land in the area around the statue’s original location. In 1588 Pope Sixtus V had it moved to Piazza S. Marco and then to its current site in Piazza del Campidoglio in 1592. Marforio was known to engage in back-and-forth mocking debates with Pasquino.

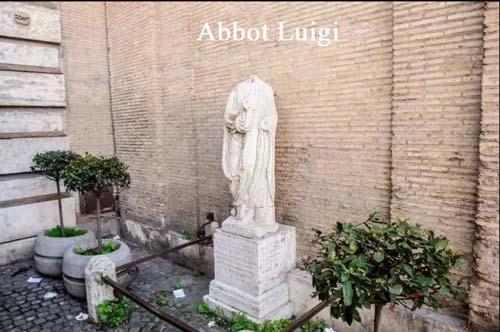

Abbot Luigi

This headless statue of a man in a toga dates from the late imperial era and can be found in Piazza Vidoni, next to the church of S. Andrea della Valle. The statue probably represents a magistrate or an orator and was named popularly after the sacristan of the nearby church of SS. Sudario.

Found during excavations near the Theatre of Pompey, the statue was moved to various locations around Rome and has been at its current site since 1924. An inscription on its pedestal reads: “Along with Marforio and Pasquino, I conquer eternal fame for urban satire.”

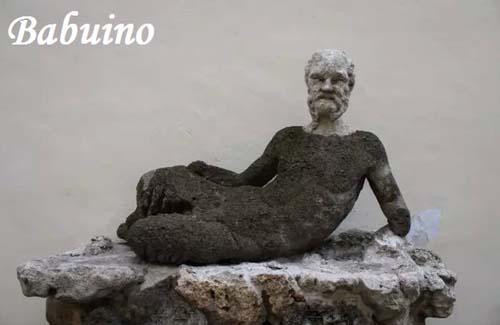

Babuino

Located beside the Chiesa di S. Atanasio dei Greci, the statue depicts a reclining Silenus, the half-man, half-goat from ancient Greek mythology. The monument was built in the late 16th century for the wealthy merchant Patrizio Grandi who, according to the then custom, obtained free water for personal use in exchange for donating the fountain to the city.

Romans considered the representation of Silenus ugly, resembling more a baboon, or “babbuino”, than a satyr. The name stuck and the street – originally named Via Clementina in honour of Pope Clement VII Medici (1523-1534) – became known as Via del Babuino.

Il Facchino

This statue of man wearing a cap and carrying an “acquarolo” barrel of water from the Tiber was created in around 1580, to a design by Jacopo del Conte. The facchino or porter was originally sited on Via del Corso, on the main facade of the Palazzo De Carolis Simonetti, but in 1874 it was moved to its current position on Via Lata, to the side of the same building, now the Banco di Roma.

With its flat beret hat, the statue’s face is badly damaged due to vandalism as it was once thought to be a caricature of Martin Luther, the German theologian who rebelled against the Catholic church and initiated the Protestant Reformation in 1517.