RIC trilateral cooperation needs enhancement

Andrey Kortunov

Obviously, the future of Eurasia largely depends on China and India. These two nations demonstrate remarkable resilience in their economic, technological, political, cultural and spiritual growth and maturation. Undoubtedly, their regional, continental and global roles will continue to evolve. Beijing-New Delhi relations have had, and will continue to have, a profound impact on the Eurasian and worldwide international order.

Nothing in their history should prevent these two Eurasian giants from working together for their own benefit and the good the continent. China and India have never tried to conquer each other. For many centuries they were engaged in extensive trade (Maritime Silk Road), exchange of philosophical and religious ideas, and sharing of innovations. There is a solid foundation for a deep and comprehensive China-India cooperation.

However, in the middle of the 20th century, the two nations became involved in painful territorial disputes. For more than 60 years, Beijing and New Delhi have experienced a number of border clashes, including the ones in May-June of 2020 and in December of 2022. Today, Indian politicians seldom miss a chance to mention Beijing’s alleged attempts to “encircle” India by supporting Pakistan and by expanding the “String of Pearls” trade and military infrastructure around India. In China, there are complaints about India opening the way for US political and military penetration into Eurasia through various bilateral US-India arrangements as well as through multilateral Washington-led initiatives like Quad (US, India, Japan, Australia) and I2U2 (US, India, UAE and Israel) wrapped into the anti-Chinese concept of “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.”

This uneasy state of affairs between Beijing and New Delhi has a profound impact on all Eurasian nations, including Russia. Moscow could extract significant benefits from the competition between its strategic partners by playing one power against the other. However, this would be short-sighted and reckless since the trust of both nations is crucial. The worst thing for Moscow would be to lose the trust and goodwill of one or both of the two Eurasian giants. Moreover, strained China-India relations would inevitably put rigid constraints on institutional prospects of inclusive multilateral initiatives in Eurasia and in the world at large, including the SCO, BRICS. Finally, this strained relationship creates lucrative opportunities for nonregional powers to play more prominent roles in and around Eurasia.

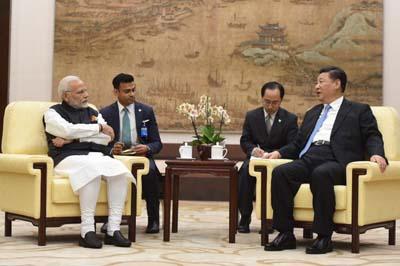

Can Moscow make a meaningful contribution to an improvement in China-India relations? The trilateral Russia-India-China (RIC) format has existed for more than 20 years, but it has been gradually overshadowed by BRICS and the SCO. However, maybe the time has come to put more emphasis on RIC.

For instance, Moscow could offer Beijing and New Delhi joint trilateral development, transportation and research projects in the Russian sector of the Arctic region. Trilateral cooperation would also make a lot of sense in the Russian Far East. The current Moscow-Beijing plans imply that the Chinese northeast province of Jilin will use the Russian seaport of Vladivostok as a domestic transit point. Reaching this seaport via rail, products from Northern China will be further shipped to Southern China by ship. Nothing should prevent businesses in Jilin, and also in adjacent Heilongjiang, from having use of Vladivostok to get convenient access to sea routes leading to South Asia, and India in particular.

Russia is a major supplier of hydrocarbons to Eurasian markets, and China and India are one of the largest consumers in these markets. The three parties should coordinate their respective energy transition strategies in a more practical and comprehensive way. An exchange of experience in renewable energy generation is definitely worth considering. Russia is now implementing large-scale nuclear power plant projects in India (Kudankulam) and China (Tianwan and Xudapu). This experience can be used for even more ambitious trilateral projects with the ultimate goal of building a shared Eurasian energy system.

Trilateral cooperation would make sense in agriculture as well – Russia continuously boosts its food exports, while both China and India are likely to face growing food stock demands from their rapidly growing middle class with changing food consumption patterns. Trilateral coordination might help stabilize the Eurasian food markets. Russia is the leading fertilizer exporter in Eurasia, India is the second-largest fertilize importer in the world, while China is both an exporter and importer. A Moscow-New Delhi-Beijing “fertilizer partnership” could shape the future of international trade of this important commodity.

Trilateral consultations on strategic stability would not only contribute to world peace and security, but also build trust and mutual confidence between Beijing and New Delhi. Other security related problems to be discussed in the trilateral format could include the challenge of international terrorism rooted in religious fundamentalism.

Needless to say, Russia is not the only country that would gain a lot from an improved China-India relationship. Therefore, the geometry of multilateralism involving Beijing and New Delhi should vary depending on specific issues to be addressed. Both BRICS and the SCO in their current compositions might be a bit too crowded and too diverse to discuss the most sensitive and potentially divisive problems. However, a number of ad hoc RIC+ formats deserve serious consideration. To handle the energy agenda, RIC members may engage Iran. It would be hard to discuss fertilizers without Brazil on the import side and Belarus on the export side. For a discussion on global and regional nuclear stability, engagement of Pakistan would be more than essential. A minilateralism mechanism that is flexible and problem-focused would hopefully help pave the way to more stable China-India relations.

The writer is academic director of the Russian International Affairs Council