Middle East’s efforts to defuse tensions merit Western attention

Alistair Burt

What a difference a few weeks makes. Since my highlighting, in a July column, the harsh media spotlight under which the US decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan was already being seen in London, we have had to confront the reality of the consequences.

While by far the most painful aspect has been the impact on the ground in Kabul and beyond, the political and diplomatic fallout is currently of a degree of seriousness to rival the bitterness of Brexit internally in the UK, and with close partners abroad.

Government departments and Cabinet colleagues have engaged in a harsh war of words that, in the long term, will benefit no one, as anger, frustration, grief and embarrassment mingle in a mess not confronted in the UK since the Suez Crisis of 1956. The Ministry of Defense and the Foreign Office differ over what was anticipated: Defense Secretary Ben Wallace says it was obvious to him that the fall of Kabul would be quick, which is not how Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab saw it as he reported to a parliamentary committee last week. As the UK public considers, with much sympathy, the plight of those “left behind” — including UK nationals, Afghans who worked with the UK and who may be at risk, and others including prominent human rights activists and women — the consequences of such differing perspectives are not merely for retrospective debate in an inevitable inquiry into what happened; they affect real policy implications, and possibly careers, right now.

The House of Commons listened in silence — a mark of respect — to a former soldier and now chairman of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee, Tom Tugendhat, as he movingly described his feelings of regret and abandonment at decisions that left his Afghan partners fearful for their lives and his lost comrades’ sacrifice questioned.

As well as the UK government fighting itself, the Commons debate also highlighted unusually harsh criticism of the US, which matched unfortunate rhetoric allegedly from Downing Street about President Joe Biden. Comments from UK defense forces about the US role and decisions made during the last days in Kabul brought swift defensive retort in Washington. To prevent a bad situation being made worse, this degree of rift must be nipped in the bud quickly. Whatever has happened, only the enemies of the UK, the US and the West generally can gain from a serious rupture between these closest of military, security and intelligence partners, which have a worldwide reach against multiple threats.

The striking thing to date — though perhaps understandable — is the degree to which analysis has focused on introspection. What does all this mean for the West? What are the implications for our foreign policy and interests? As always, it is all about us. There has been less analysis of what this might mean in those regions where Western engagement and involvement over such a long period has left its mark, and what exactly the events in Afghanistan might mean.

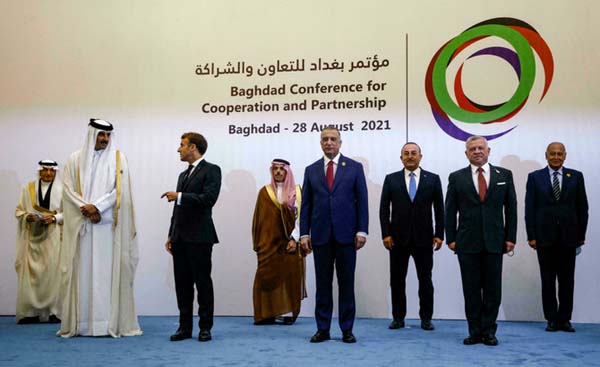

But, having said that and knowing that one of the implications has surely to be “less West” going forward, I was surprised so little attention has been paid here in terms of media coverage and comment to the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership just days after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban. Perhaps the Anglo-Saxon media was reacting against the attendance of French President Emmanuel Macron, but it does seem to illustrate that old attitudes will take some time to wear away.

Current activity in the region, where adversaries are reaching out tentatively to one another, is worth noting and supporting.

The West’s future engagement in the Middle East and North Africa is going to be different in character. Accordingly, current activity in the region, where adversaries are reaching out tentatively to one another, is worth noting and supporting. No one is expecting a surprise and sudden breakthrough, and there are differing motives and expectations of talks that no one should be naive about, but the patient attempts of Baghdad to bring Saudi and Iranian representatives together culminated at the recent conference — the first meeting of their respective foreign ministers for five years.

The summit was not perfect, and there were absences, but in a region where the issue of foreign engagement has been so divisive and where the implications for states that have lined up for and against such engagement are significant, these efforts at forging some kind of regional understanding to defuse tensions and avoid further catastrophe deserve fuller attention in Western capitals. That it is Baghdad hosting — knowing what it presently still combats domestically, and what it has endured — says much for President Barham Salih’s determination to use the dark period of the last 40 years as a springboard to something better.

In a region where our historic imprint has been so visible, it would be good to see rather greater UK and European awareness, acknowledgement and support for these steps.

The writer is a former UK MP who has twice held ministerial positions in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office — as parliamentary undersecretary of state from 2010 to 2013, and as minister of state for the Middle East from 2017 to 2019.