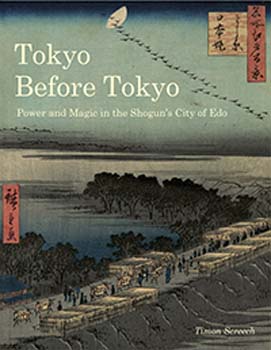

‘Tokyo before Tokyo’: A guided tour through Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Edo

Martin Laflamme

Taipei: Tokyo was not always one of the world’s great cities. In fact, for much of Japan’s history, it was a backwater town. This perception was particularly acute from Kyoto, the seat of the imperial court for centuries and the epitome of all things civilized. In the poetry of its aristocracy, the entire Kanto Plain was invariably depicted as a remote realm of uncouth barbarians.

The rise of Tokyo, then known as Edo, began in the early decades of the 17th century. Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616) had just unified the country after more than a century of civil war, and rather than move his government to Kyoto as some had done before, he chose Edo, taking his cues from the Minamoto clan, who had established theirs nearby, at Kamakura in 1185.

Until then, the development of Edo had been driven by military necessity. But with the country at peace, a different approach was necessary. Unfortunately, urban ideals based on time-honored traditions adopted from China, which Ieyasu and others looked to for inspiration, were not meant for existing cities, but for those built from scratch. To name one example, they required that constructions be laid out on a grid, oriented along a north-south axis, with streets interlocking at 90 degrees. The palace had to be positioned at the northern end, facing the sun, with the city’s main thoroughfare running south from there. The entire agglomeration had to reflect the symmetry of the human body and thus, a market or temple on the East side of town necessitated a matching one on the West side.

By comparison, growth in Edo had spread in rough circles, around the moats of the castle. A grand Chinese design was not possible, at least not entirely. The compromise was to build districts on a grid and many, such as Nihonbashi and Ginza, remain this way today.

Even more important to traditional urban planning was the need to follow the tenets of Chinese geomancy. This meant the taming of Ki, an invisible life force that is neither positive nor negative, but becomes one or the other as it flows above sites with these respective qualities.

Ki generally moves from the northeast, which means that this cardinal starting point must be appropriately guarded. This is why it became customary to build at least one temple facing that direction. For Edo, Sensoji Temple in Asakusa briefly served that purpose until it was augmented by Kaneiji Temple, in Ueno. This belief in Ki also explains why activities deemed impure, such as tanning hide, killing animals or executing criminals, had to be conducted in places like Senju, outside the city limits and beyond the protection of these temples. Likewise with the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter which, after the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657, was relocated some distance north of Asakusa.

A professor of the history of art at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, Timon Screech is a highly knowledgeable guide to Ieyasu’s Edo. His narrative is generously illustrated, albeit at times with images that are frustratingly small. Today, very little of Tokyo’s past remains standing, but the original footprint is still there. With “Tokyo Before Tokyo,” Screech shows us where to look.