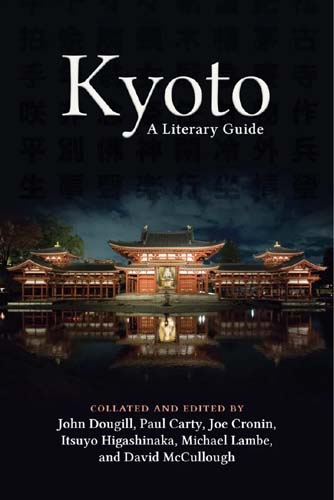

A passion project that became a literary journey through Kyoto

Stephen Mansfield

When a group of friends, academics, translators and professors of literature formed a monthly circle dedicated to studying Kyoto’s sumptuous literary legacy, they likely did not expect their passion and commitment would span a 10-year period.

Astounded to find no English anthology of literature on the city, they decided in the spring of 2017 to produce their own. The result, “Kyoto: A Literary Guide,” is a slim, highly filtered presentation of work, largely verse, that begins its travel through time with the crafted words of privileged courtiers, counselors and ladies-in-waiting of the Heian Period (794-1185).

A typical sampling, taken from Izumi Shikibu’s beautiful poem, reads as such: “Reflecting on my life / the fireflies above the stream / seem to be my yearning soul / wandering free of my body.”

From the verse of ancient court ladies and imperial consuls, who devoted much of their time to pondering the descent of a petal or the trembling of a leaf, the book teleports readers through the literary history of Kyoto until we reach the modern day. “Koryu-ji’s ten-foot-tall / thousand-armed Kannon / a radiant Buddhist Army Knife of Compassion / waiting a thousand years / ready to hand over the goods,” writes Kyoto resident Ken Rogers in his startling poem from 2017.

Many of the poems place the beauty and plenitude of nature against the fragility of life. There are few instances of hubris or narcissism, the words of Fujiwara no Michinaga (966-1028) an exception. An influential power broker of the Heian Period, Fujiwara acknowledges his authority, comparing himself to the enduring elements of nature and his mastery over it: “This world, I think / is indeed my world / like the full moon shining / bright and undiminished.”

One of the names that stands out among the editors and translators who contributed to “Kyoto” is that of John Dougill, a writer and scholar who has lived in Kyoto for over 20 years. As the group’s driving force, Dougill came up with the idea for the book to commemorate their 10 years together. Of the collaborative process, he says: “One person put forward a suggested translation. We discussed, disagreed and enthused. The result was a rewriting. On occasion, someone would have strong feelings and others would demur or compromise.”

Echoing Dougill’s comments, fellow contributor Paul Carty emphasizes that “everyone brought ideas to the table.” Working incessantly on revising poems, however, would seem a formula for frayed nerves.

“The only reason we did not kill each other is that, even though every member had strong opinions, we kept relations warm,” Carty says. One painful aspect of finalizing the book was that they “left so many wonderful poems on the editing room floor.” A consoling thought might be that anthologies rarely claim to be definitive.

Itsuyo Higashinaka, a Lord Byron specialist, was the only Japanese member of the group. When I asked Higashinaka about cultural geography, he recognized that Tokyo has indeed taken over as the wellspring of contemporary literature. And yet, he notes, “Kyoto dominates when it comes to classical Japanese poetry.”

Joe Cronin, another member of the group, expressed gratitude for Higashinaka’s presence: “Having one native Japanese was very valuable at times when we unthinkingly fell into unjustified assumptions.” Living in Kyoto for more than 30 years has made Higashinaka a stickler for conciseness, and according to Cronin, “one of the most concerned in the group about the accuracy of the translation.”

Michael Lambe is another long-term Kyoto resident who regards the city as his home. The “spirit of the original pieces” was maintained by repeatedly checking sources with the aim of producing translations that satisfied everyone, Lambe says. “I think this made us very careful readers indeed and helped us to notice the finest details that a solitary translator might easily overlook or simply dismiss as too difficult.”

Many of the poems have useful, but not long or burdensome footnotes. The following is a fine example of the associative depth contained in short lines, which might be passed over by the casual or uniformed reader.

For the poem by Fujiwara no Shunzei (1114-1204), which reads, “The moon shines bright / on Mitarashi Stream / shadows cover the ice / like indigo sleeves,” the footnotes tell us that indigo sleeves were once worn by sacred dancers.

Placed in the context of so much verse, the extracts from novels read like prose-poems, works of striking imagery. In a section from his 1956 novel, “The Temple of the Golden Pavilion,” Yukio Mishima describes Kinkakuji as a “melancholy and delicate structure … resembling a gorgeous corpse.” It’s a comparison unlikely to have crossed most minds.

Some of the entries are exacting documents of time. Taikyoku Unsen, who surveyed the destruction of Kyoto during the Onin War (1467-77), gives us the devastating image of an “old temple with many pines,” its grounds “now an army camp.” This returns us to the ancient, pathos-soaked sensibility of aware no mono, a term denoting the fragile, grievous beauty of impermanence, a state of reality in which the only constant is change.

My only serious criticism of this book is that, being of such exquisite quality, it is so short. In an extract from “Essays in Idleness,” 14th-century author Yoshida Kenko writes that “life is wonderful because it does not last.” I would argue that the opposite is true for writing, which is made wonderful by its perdurance.