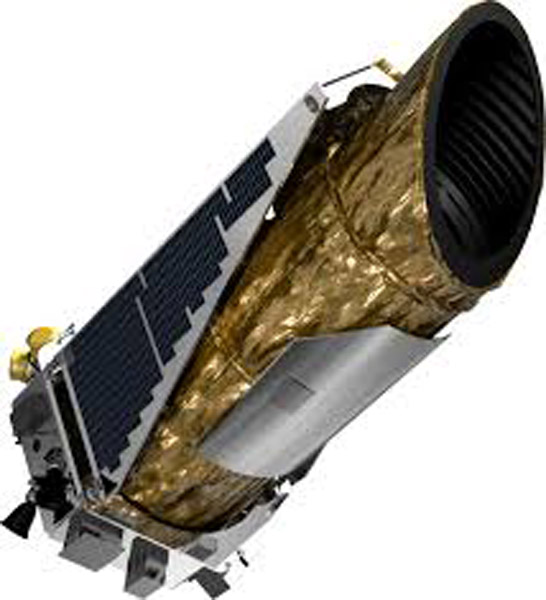

NASA’s Kepler reborn, makes first exoplanet find of new mission

NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft makes a comeback with the discovery of the first exoplanet found using its new mission — K2.

The discovery was made when astronomers and engineers devised an ingenious way to repurpose Kepler for the K2 mission and continue its search of the cosmos for other worlds.

“Last summer, the possibility of a scientifically productive mission for Kepler after its reaction wheel failure in its extended mission was not part of the conversation,” said Paul Hertz, NASA’s astrophysics division director at the agency’s headquarters in Washington. “Today, thanks to an innovative idea and lots of hard work by the NASA and Ball Aerospace team, Kepler may well deliver the first candidates for follow-up study by the James Webb Space Telescope to characterize the atmospheres of distant worlds and search for signatures of life.”

Lead researcher Andrew Vanderburg, a graduate student at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, studied publicly available data collected by the spacecraft during a test of K2 in February 2014. The discovery was confirmed with measurements taken by the HARPS-North spectrograph of the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in the Canary Islands, which captured the wobble of the star caused by the planet’s gravitational tug as it orbits.

The newly confirmed planet, HIP 116454b, is 2.5 times the diameter of Earth and follows a close, nine-day orbit around a star that is smaller and cooler than our sun, making the planet too hot for life as we know it. HIP 116454b and its star are 180 light-years from Earth, toward the constellation Pisces.

Kepler’s onboard camera detects planets by looking for transits — when a distant star dims slightly as a planet crosses in front of it.

The smaller the planet, the weaker the dimming, so brightness measurements must be exquisitely precise. To enable that precision, the spacecraft must maintain steady pointing. In May 2013, data collection during Kepler’s extended prime mission came to an end with the failure of the second of four reaction wheels, which are used to stabilize the spacecraft.

Rather than giving up on the stalwart spacecraft, a team of scientists and engineers crafted a resourceful strategy to use pressure from sunlight as a “virtual reaction wheel” to help control the spacecraft. The resulting K2 mission promises to not only continue Kepler’s planet hunt, but also to expand the search to bright nearby stars that harbor planets that can be studied in detail, to help scientists better understand their composition. K2 also will introduce new opportunities to observe star clusters, active galaxies and supernovae.

Small planets like HIP 116454b, orbiting nearby bright stars, are a scientific sweet spot for K2 as they are good prospects for follow-up ground studies to obtain mass measurements. Using K2’s size measurements and ground-based mass measurements, astronomers can calculate the density of a planet to determine whether it is likely a rocky, watery or gaseous world.

“The Kepler mission showed us that planets larger in size than Earth and smaller than Neptune are common in the galaxy, yet they are absent in our solar system,” said Steve Howell, Kepler/K2 project scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “K2 is uniquely positioned to dramatically refine our understanding of these alien worlds and further define the boundary between rocky worlds like Earth and ice giants like Neptune.”

Since the K2 mission officially began in May 2014, it has observed more than 35,000 stars and collected data on star clusters, dense star-forming regions, and several planetary objects within our own solar system. It is currently in its third campaign.