Chinese people’s reaction to Abe’s death is real

Wang Wen

The Chinese society’s mixed, complicated reaction toward the assassination of former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe is normal and real. Be it joy of many netizens, the warning some public opinion elites issued about being careful not to be taken advantage of by external forces, or some people’s positive appraisal of Abe’s political achievements, they are all parts of China’s complicated public opinion response, providing a window for the outside world to understand better China’s complexity.

The century-old feud between China and Japan determines it’s impossible to expect Chinese netizens to feel deeply grieved about Abe’s death. It’s even less likely to ask China to express “sadness” by announcing a one-day national mourning as India did or flying the national flag at half-mast as the US did. China will not do so, even if just for putting on a “show.”

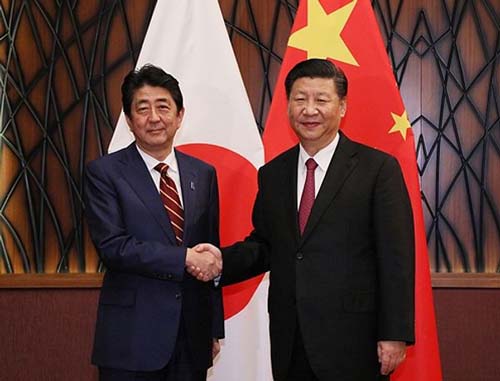

President Xi Jinping on Saturday sent condolences to the Japanese government over the passing of Abe. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs also made an appropriate evaluation of what Abe had done for the improvement of the China-Japan relations. This shows China’s cultural etiquette and political rationality, and represents China’s official stance over Abe’s death.

Some foreign media outlets translated a lot of comments by Chinese netizens rejoicing in the assassination of Abe to mock Chinese people’s “rudeness” and “ruthlessness.” This is a misunderstanding and prejudice against Chinese people.

In China’s public opinion field, many elites have given positive comments on Abe’s political achievements. One of my friends, a senior media figure in Shanghai, even called Abe “the greatest statesman in East Asia in the 21st century.”

In my opinion, as long as the comments are made on reasonable grounds rather than being spurred by an overly worshipping Japan or pro-Japan sentiment, they could be understood and acceptable in Chinese society.

Following the abnormal death of a dignitary of a foreign country, the Chinese elites have the ability to transcend emotion, calmly analyze the international issue and evaluate it comprehensively regardless of whether the dead one was a Japanese or not.

A Chinese saying in the Confucian classic Book of Rites, also known as the Liji, compiled around the Warring States Period (475BC-221BC) goes, “When there is a funeral in the neighborhood, don’t sing work songs when pounding rice, and don’t sing in the alleys.”

Some intellectuals cited this to educate the netizens, asking them to view Abe’s death with rationality – “Abe has passed away, why not express grief toward his death?”

However, it seems this doesn’t work. For most Chinese, the situation depicted in the ancient Chinese book shouldn’t be applied to Japan. The joy of some Chinese toward Abe’s death shows their true feelings about Japan. It’s a natural and frank reaction to the sad and tragic history of Chinese people being killed, bullied and suppressed by Japanese aggressors in the first half of the 20th century as well as to Abe’s attitude of following the US in containing China and frequently visiting the Yasukuni Shrine, which enshrines Japan’s infamous Class-A war criminals who symbolized Japan’s war atrocities and militarism during World War II.

Japanese prime ministers, Abe in particular, for many years, had on one hand claimed they would reflect on Japan’s war history, while on the other paying tribute to the Yasukuni Shrine, taking a pro-US stance and interfering in the Taiwan question. This is definitely unacceptable and cannot be forgiven by the Chinese people.

The Chinese people in fact are not afraid of their sentiment being noticed by the outside world. They are not very sophisticated in general, and they dare to express explicitly their love and hate. Foreigners’ goodwill to China will be remembered from generation to generation if these foreigners, such as Canadian doctor Norman Bethune who came to help the Chinese people during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), are friendly to China. If a foreigner treats China badly, he or she won’t gain Chinese people’s leniency even when they die.

The Chinese people value people’s reputation after death. They believe life is short but death is eternal. Some infamous figures have been spurned with scorns for thousands of years by Chinese people, such as Qin Hui, a chancellor of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) in Chinese history and also a big traitor. Till today, statues of Qin and his wife are still kneeling in front of the tomb of Yue Fei, a contemporary of Qin and a heroic general who was framed and murdered by Qin.

International politicians may also have to think: If they continue to contain China, what will they receive, after their death, from the 1.4 billion Chinese people?

Today’s China is no longer so elusive. There are ways to express almost all emotions, which symbolize Chinese society’s progress. Differences can also be accommodated in the Chinese public opinion environment, which can be regarded as a Chinese-style cultural tolerance.

The writer is executive dean of Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China