Can the US and China avoid a catastrophic clash?

Daniel R DePetris

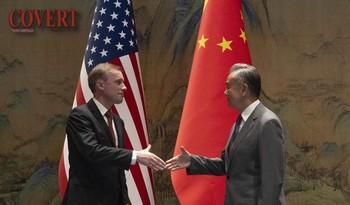

New York: Last week, US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan travelled to China for a multi-day trip in an attempt to keep relations between Washington and Beijing on a somewhat even-keel as the United States prepares for a political transition in several months’ time.

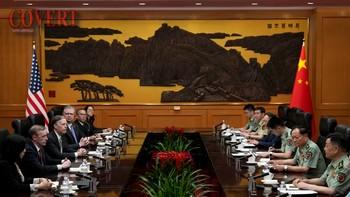

The trip was notable in several respects. It was the first time in eight years that a US national security adviser made the trip to Beijing, and Sullivan managed to grab a meeting with General Zhang Youxia, the vice chairman of the Central Military Commission.

The mere fact that this specific meeting occurred, after a two-year freeze in communications with its military officials, suggests that China’s President Xi Jinping is as interested in maintaining stability over the proceeding months as the Biden administration is.

The readouts of the conversations don’t tell us much. On the US side, the word of the day was “responsibility,” as in both superpowers have a responsibility to ensure the competition between them doesn’t veer into a conflict. While this phrase has taken on a robotic-like character over the years, it happens to be true.

The consequences of a direct US-China conflict, either over Taiwan, the disputed shoals of the South China Sea or by sheer miscalculation, are unfathomable. One war-game conducted earlier in the year assessed that tens of thousands of US service members would be lost in addition to dozens of ships and hundreds of aircraft. The economic repercussions would be just as gargantuan, with perhaps as much as 10 per cent of global gross domestic product wiped out.

Systemic rivalry aside, the US and China don’t have an interest in flirting with such a catastrophic scenario. To the extent Sullivan’s meetings reinforced this theme, then they were time well spent.

But nor is there much room for problem-solving among US and Chinese officials at this particular time. Indeed, just as Sullivan stressed the urgency of responsibly managing relations, he also made it clear that Washington wasn’t going to reorient its China policy.

American technologies that could contribute to the modernisation of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will continue to be restricted. Sullivan called out China for its repeated use of so-called “grey zone” tactics around the Sabina and Second Thomas Shoals, designed to interrupt Philippine re-supply missions. Taiwan will remain the biggest point of contention, with Sullivan yet again denouncing any moves by China to settle the issue by force.

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi was equal parts scathing and diplomatic during his time with Sullivan, arguing that the United States needed to start treating China as an equal rather than a systemic competitor. In fact, Chinese officials completely disagree with the notion that the United States and China can be a competitor and a partner at the same time.

On the South China Sea, Beijing wants the United States to stay out entirely. Xi remains emphatic that US export controls are as much about preventing Chinese economic development as they are about constraining the PLA. Short of outright US capitulation to Chinese demands, there is little Washington can do to assuage Beijing on any of these matters.