What drives the revival of the ancient Silk Road

Ding Gang

Traveling along the Hexi Corridor that connects Northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region with other regions in China, I was deeply impressed by three aspects. Firstly, the bustling transportation along the corridor caught my attention. Secondly, I noticed that each town has gained its unique specialty. For instance, Zhangye city in Gansu Province has gained recognition as one of the top 10 vegetable production bases in China.

And the third point is that people’s lives and work here are closely linked to Xinjiang. When choosing a place to work, many young people from these rural areas no longer prefer inland or coastal cities. Their preferred choice is Xinjiang. In the night markets in towns in Gansu and Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, you can find many young people from ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang running their businesses.

Locals told me that this is because Xinjiang’s economy recovered quickly after the COVID-19 epidemic, and since its agriculture and manufacturing industries are on the rise, stable jobs are easy to find. Many young women have gone to work in textile factories in Xinjiang.

These changes reflect Xinjiang’s increasing importance in China’s overall development strategy. On November 1, the Xinjiang Pilot Free Trade Zone (FTZ) officially started operations, marking a new historical starting point for the region’s deepening of reform and opening-up.

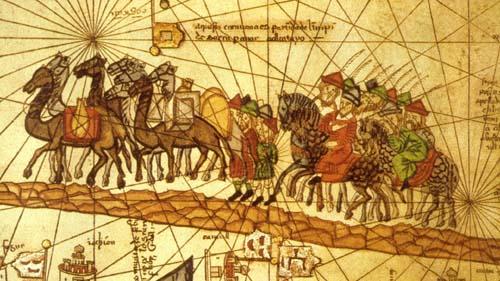

This is an important strategic shift for China’s economy and its opening-up to other parts of the world. The ancient Silk Road will showcase its vigor and charm at this new historical point in the process of further expanding and deepening globalization.

The FTZ is put forward amid the US’ and Europe’s containment and sanctions on Xinjiang manufacturing, especially cotton. It is, at the same time, in accordance with the grand strategy of transferring Made-in-China to the western part of the country, especially with the promotion of the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Take cotton produced in Xinjiang as an example. It is globally recognized as a high-quality natural fiber raw material, and its production accounted for about 20 percent of the world’s total. Cotton from Xinjiang is an important raw material that ensures the healthy and sustainable development of China’s and even the global textile industry.

The US government’s suppression of Xinjiang cotton and its products essentially aims not only to try to interrupt China’s textile industry chain and curb the development of China’s textiles in the global market, but also seriously undermine the pillar industries of China’s manufacturing and shake the foundation of China’s economy and cooperation under the BRI.

However, although the US’ sanctions have put pressure on Made-in-China, ironically, they only accelerate the upgrading and transfer of China’s manufacturing. This is similar to the case when the US’ technological blockade of high-end chips accelerated the innovation and application of China’s homemade chip.

China’s manufacturing has encountered some problems in recent years, including the rising labor costs that have had a greater impact. However, the production capacity of the manufacturing industry has not seen a significant change. The country is now beginning to reinforce the foundation for the long-term development of the manufacturing industry due to the need for economic transformation.

The upgrading of Xinjiang industries is first and foremost based on the layout of a coordinated national strategy, which is based on Xinjiang’s natural advantages and development potential. The Xinjiang local government has proposed to develop eight industrial clusters, including oil and gas, coal-related industry, green mining, grain and oil, cotton and textile, organic fruits and vegetables, livestock, and new energy and materials.

Such a great enhancement is attracting tens of thousands of enterprises from the inland provinces to invest in Xinjiang, as well as more young people to live and work in Xinjiang. Perhaps, in a few years, a “special economic zone” of Chinese manufacturing like Shenzhen will appear in Xinjiang.

China’s economy is now in a difficult transition period, which includes external pressure, especially from the US and the West, preventing Chinese companies and China’s manufacturing from going global. But when you look at Xinjiang, what you see is the rise of the western part of China in interaction with the entire Central and South Asia.

Peter Frankopan, a historian at the University of Oxford, concludes his book The Silk Roads: A New History of the World by predicting that the Silk Road is reviving.

We should also remember the words from Sand and Foam by Lebanese-American poet Kahlil Gibran, “I would walk with all those who walk. I would not stand still to watch the procession passing by.”

The writer is a senior editor with the People’s Daily, and currently a senior fellow with the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China