US foreign economic policy is dividing global economy

Ali Farid Khwaja

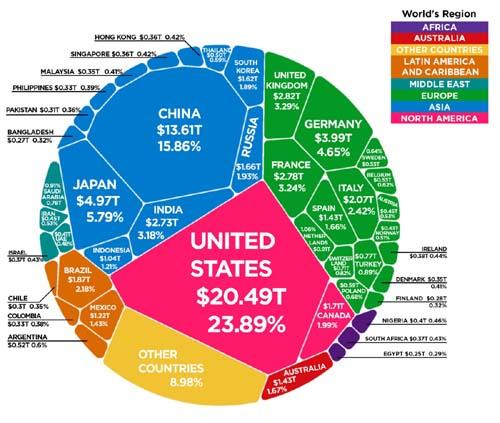

The US foreign policy shift towards China can end up creating a very divided global society, one filled with intrigues, conspiracies, and suspicion. The riots in Sri Lanka and Pakistan’s current political scene are examples of this. Such fissures will not be limited to the emerging markets but are likely to have a wider impact.

We know how this story plays out as this has happened before – the Cold War and the great divide of the Iron Wall. While economically, the US certainly benefits from a nationalistic agenda in the short term, in the long run, however, it would trigger changes which would make the US and the world worse off.

While it was former US President Donald Trump who was more vocal about the use of “beggar-thy-neighbour” policy and was explicit in following a nationalist economic agenda at the expense of other trading partners, the change started much earlier in 2008, following the Great Financial Crisis. The printing of money through a combination of monetary and fiscal stimulus to boost economic growth was in a way a renege of the tacit global contract which had made the US Dollar the standard of global trade. The US Dollar, which has replaced gold as the standard, is not only the currency of the US but it serves as an anchor of the global economy. The policy shifts showed that not only the US financial institutions but also the US economy is too big to fail, and the US government can always print as much dollars as it wants to drive growth.

The US economic strategy has triggered many changes in the global economy in general and for the emerging markets in particular.

Firstly, it led to a twelve-year bull run in the US equities and caused underperformance of emerging markets. Historically, and according to financial theory, emerging markets are supposed to grow faster than developed markets as they have the “catch-up” trade. They have higher marginal returns from investment. De-globalization reversed this trend by triggering a capital outflow from emerging economies towards the US. According to EPRF, investments in emerging markets have declined from 14% of total global investment assetsat peak to 6.4% in 2022. This is reflected in performance as well. MSCI Emerging Markets Index has massively underperformed S&P500 and MSCI World Index. Over the past ten years, MSCI Emerging Markets Index has generated annualized returns of 2.8% versus over 40% for S&P500 and 11% for MSCI World Index. Contrary to financial theories, it has been much better to invest in the US than in emerging markets.

Secondly, de-globalization has triggered an inflationary cycle. One of the reasons why the global economy was able to enjoy a steady and secular growth trend since the 2000s was due to the benefits of excess labour in emerging markets. During the first ten years, this was able to absorb wage price pressures and later over the past ten years had started to drive global consumption demand. De-globalization means a double whammy: both cheaper supply and higher demand are restricted.

Thirdly, it has already led to reactionary consequences. The invention of and the pickup in demand for Bitcoin is a good example. Bitcoin was explicitly launched by its inventor(s) who used the name Satoshi Nakamoto as a peer-to-peer currency in order to protect against the mass printing of the US dollar by the Fed. Other countries will be forced to consider similar options. India’s move to settle trade with Russia via India Rupee is winning praise even from Pakistan.

America is built up on multiple economic, military and foreign policy relationships. However, its de-globalization moves will damage these economic connections and eventually damage the dominance of the US. It would be difficult for other countries to agree to economic policies which are not favourable to their own people and their own economies, no matter how close they are to the US. As a result, such policies will eventually erode their domestic popular support, leading to the rise of anti-US political rhetoric. What is happening in Pakistan could happen in other countries as well. A divided, hostile, angry, and suspicious world is not a happy outcome for anyone.

The writer is Chairman of KASB KTrade Securities in Pakistan and a Rhodes Scholar from University of Oxford