China-Russia Statement: A quest for diversity

Andrey Kortunov

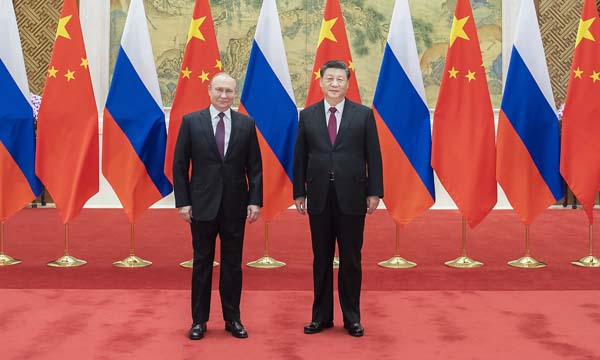

On February 4, on the sidelines of the opening ceremony of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a Joint Statement on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development. It is a rather lengthy document, outlining common approaches of China and Russia to some of the most fundamental issues of the modern world including regional and worldwide security, democracy and political inclusion, social justice and climate change, arms control and nuclear nonproliferation, national sovereignty and multilateralism.

It is not surprising that this statement has received a lot of criticism coming from Western media. Beijing and Moscow have repeatedly been accused of forging an “alliance of autocracies” threatening the West. US and European journalists, experts and politicians argue the Chinese and Russian leaders demonstrated that they do not really care about human rights or democratic institutions, do not tolerate any dissenting views or political opposition and aim to maintain their legitimacy primarily on the basis of economic security and nationalistic pride.

There is hardly anything new in these critical comments. However, the logic of Western opinion-makers deserves a closer look.

First, by labeling the two countries “global autocracies” such opinions already reveal a superficial approach of their authors. China and Russia are two very different nations; each of the two has its unique political traditions and culture, each has its own approach to managing dissent and opposition, dealing with internet and social media, integrating ethnic and religious minorities. China and Russia are like a whale and an elephant, to put them into one basket of “global autocracies” is a very questionable and misleading generalization, to say the least.

Second, there is nothing in the joint statement that would give reasons to believe that China and Russia are eager to launch an ideological war against liberal Western democracies or to question the right of the West to stick to political systems that have evolved in Western countries over the last two or three centuries. The statement underscores only the obvious: No country, and no political party or movement has the ultimate answers to all the difficult questions of social development. Therefore, there should be no hierarchy or subordination among states on the basis of how they organize their political and social lives. This, however, does not imply that there are no universal human rights, which all the states have to honor and protect. Such universal rights do exist, but they should be defined by the international community at large, not by a small group of countries proclaiming themselves as “model” democracies.

Third, China and Russia maintain that the main dividing line in modern politics is not the one between “democracies” and “autocracies,” as are often presented in the West, but rather between “order” and “disorder.” The key challenge of global politics today, as seen from Beijing and from Moscow, is about enhancing global governance within the increasingly heterogenic world. To meet this formidable challenge, the international community should regard and accept its growing diversity as an asset, not a liability. Politicians and state leaders should focus on inclusive, not exclusive, mechanisms regulating specific dimensions of global and regional economics and politics.

This is why both China and Russia expressed their firm opposition to blocks and situational coalitions based on ideological principles and aimed at marginalizing, if not containing, other international players. This opposition relates not only to such defense alliances like NATO or AUKUS, but also to more amorphous structures like Quad. Turning ideology into the main principle defining the emerging new world order would be a strategic mistake with long-term implications for all of us. If ideological divisions prevail, conquer the public and get reflected in national strategies and doctrines, these divisions will become a formidable obstacle on the way to uniting the humankind around common problems and common public goods. The weeds should be rooted out before they grow too high.

The writer is a director general of the Russian International Affairs Council.