US no longer exceptional, but it takes time to accept

Martin Jacques

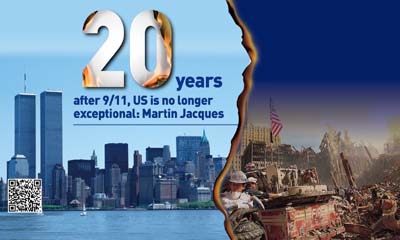

In historical retrospect, America’s reaction to the 9/11 attacks on New York’s Twin Towers was breathtakingly disproportionate. Tragic though it was, a death toll of 2,977 barely registers on the Richter scale of military conflict and acts of terrorism. If the same had happened to the magnificent Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, it might have been on the front pages of Western newspapers for a day or two, and then it would have been forgotten. But 9/11 happened in America.

The US had never experienced an invasion. The many wars that it has fought were overwhelmingly in faraway lands. This, however, happened on American territory, in New York no less. Revenge was inevitable. The American public demanded that those responsible be punished. The fact that a bunch of terrorists were responsible made any proportionate revenge unacceptable given the public outcry. America was in no mood for proportion.

Certainly, proportion was not in the mind of the Bush administration. America was the sole superpower.

Ever since the end of the Cold War, America had presided over a unipolar world. It was the global policeman. It needed to show the world who was boss, and that America could not be messed with. Proportionality was no consideration. The neo-conservative administration believed that the new century was destined to be an American Century. With the implosion of the USSR, there was not a rival in sight. This was also the Age of American Hubris: anything was possible.

There were no limits to what America could do. Rarely has a government made such a catastrophic miscalculation. The Bush administration made two fateful decisions: to invade Afghanistan in order that it could no longer be a breeding ground for terrorism; and to invade Iraq, overthrow Saddam Hussein, and turn the country into a Western-style democracy. The former at least bore some relationship to 9/11, as Al Qaeda was based there. Iraq had zero connection with 9/11. The US exploited the opportunity offered by 9/11 to remake the Middle East.

The two wars proved hugely expensive in terms of loss of life and financial cost. The Iraq war is estimated to have cost between $2 trillion and $3 trillion and the number killed to have been in excess of 400,000. The cost of the Afghan war is estimated at $2.3 trillion. There are no reliable figures for deaths in the Afghan war, but they were undoubtedly in excess of 100,000, probably far greater. The Brown University Costs of War project estimates that America’s War on Terror has cost over $8 trillion and resulted in 900,000 deaths. For what?

Both wars ended in disastrous and abject failure. After 20 years, the longest war in American history, the Afghan war saw America humiliated in a spectacle reminiscent of its retreat from Vietnam in 1975. Apart from killing Saddam Hussein, the US achieved none of its objectives in Iraq.

America’s ignominy resulted from a total misreading of the world at the turn of the century. It believed the world was unipolar when in fact it was becoming increasingly multi-polar. It thought it had the world to itself when already it was evident that China was in the process of emerging as a major global player. The consequence was one of the most remarkable demonstrations of over-reach since the World War II, or even the last two centuries.

The US learnt the hard way that its power was not infinite, that it could not do whatever it wanted, that there were severe limits to what it could achieve. And it has paid a huge price in terms of lives and dollars, and how it is regarded in the world. 9/11 and its immediate aftermath marked Peak America and by engaging in reckless over-reach the US has over the last two decades served to greatly hasten its own decline. That decline is now more or less universally recognized, even in the US, though in 2001 the very mention of the word would have been dismissed as absurd.

9/11, and the 20 years since, are a textbook example of the chronic failure of American governance. There was the failure to understand the world, a basic prerequisite for any superpower. Then, even when it became clear that the wars were failing, successive presidents – Bush, Obama, and Trump – failed to muster the courage to acknowledge that a huge mistake had been made and pull out. Twenty years is an extraordinarily long time for such a lesson to be learnt.

There is another factor at play here. For the best part of two centuries, Americans have believed that being No.1 in the world is part of the country’s DNA. An admission of failure would, as Biden has found, not have gone down well with its people. America is a prisoner of a past that is in rapid retreat. No longer exceptional it is becoming a normal country. But it will take a very long time before it learns to accept that fact.

The writer was until recently a Senior Fellow at the Department of Politics and International Studies at Cambridge University. He is a Visiting Professor at the Institute of Modern International Relations at Tsinghua University and a Senior Fellow at the China Institute, Fudan University.