What does China expect from the new Afghan government?

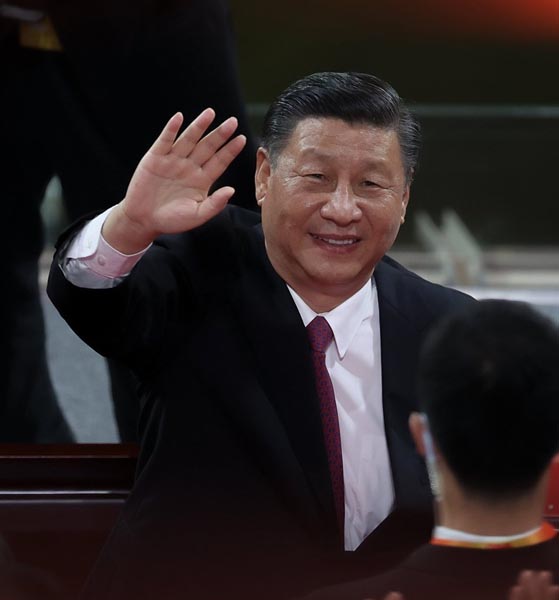

Hu Xijin

I think what we can expect most from the new Afghan government should be as follows, and in that order:

First, they draw a clear line against the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) and other terrorist forces that pursue “Xinjiang independence,” and they do not support any activities aimed at destabilizing China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Second, they form an open, inclusive and broadly representative government, bringing a complete end to the civil strife for a permanent peace. They should also contribute to ease the regional situation and promote the well-being of the Afghan people, providing no more pretexts for possible future interventions by outside forces.

Third, they keep distance from the US and other forces that turn out to be hostile to China. They should refuse to act as a pawn for those forces to jeopardize China’s strategic interests. Instead, we hope they are committed to developing friendly and cooperative relations with China and other neighboring countries and integrating into the common cause of regional peace and development.

Fourth, they promote the moderation of basic domestic social policies, boost the development of human rights, protect the rights of women and children, and turn Afghanistan into a moderate Islamic country.

In my opinion, such an order is very crucial. China does not have strength or interest in “reforming” Afghanistan, because that will not be in line with the country’s basic diplomatic concept. China’s national interests must be the starting point for our review of the ever changing situation in Afghanistan. In fact, this applies to all countries.

Some people in China now use human rights issues, such as women’s rights, as the primary standard to decide if they will like the new regime in Afghanistan. Such a focus of attention is a common perspective in modern society, and it does have its own intrinsic and realistic logic. But it is impulsive and irrational to decide whether to develop relations with the new regime in Afghanistan on the basis of that standard alone.

In fact, “human rights diplomacy” is usually used as a geopolitical lever by countries even like the US. For example, Muslim-majority countries such as Iran and Syria are much more secular than Saudi Arabia. But the US has never attacked human rights issues, including women’s rights issues, in Saudi Arabia. Yet the Americans have pointed their moralizing finger at similar problems in Iran and Syria as an excuse for US intervention.

The US hates terrorism on one hand and discriminates against Muslims on the other. I have watched a video from the US in which a female speaker drew a full house by thoroughly denying and smearing Islamic civilization. However, American people are specifically concerned about the “human rights” of Muslims in Xinjiang, slandering China’s anti-terrorism actions there as “genocide.”

Noninterference in other countries’ internal affairs is indeed the golden rule of China’s diplomacy. But the practical effect of judging the Taliban from an ethical perspective and asking China to disdain Taliban diplomatically is to cater to Washington’s policy in Afghanistan and to benefit the US. China will surely work to insert a positive influence on the Afghan administration. However, we cannot take the US’ national interests as a starting point. We do not dance to Washington’s drumbeat.

The US launched the war in Afghanistan in 2001 and then abandoned the country last week in 2021. Such a rude act has taken countless Afghan people’s lives and harmed their rights. Chinese people are not obliged to clean up the messy situation left by the US’ failed Afghanistan policy. Nor are we obliged to help pull Washington out of the pit it had dug, and then jump into it ourselves.

We need to calmly observe the Taliban’s rule and should not rush to conclusions in any direction. Meanwhile, we should open up the channels of contacts with the Taliban and prepare for advancing China’s national interests in the future situation in Afghanistan.

The writer is editor-in-chief of the Global Times